Artificial intelligence has quickly woven itself into the daily lives of teenagers offering instant answers, emotional support, and, in some cases, a listening ear that feels more reliable than human connections. But beneath this veneer of helpfulness lies an unsettling truth: recent research reveals that when AI interacts with vulnerable young users, it can sometimes deliver dangerously misguided advice. From unsafe dieting tips to instructions on substance use, and even assistance in drafting suicide notes, these conversations raise urgent concerns about the ethical, legal, and social responsibilities of AI providers.

As Imran Ahmed, CEO of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, warned after his team’s recent investigation:

“Within minutes of simple interactions, the system produced instructions related to self-harm, suicide planning, disordered eating, and substance abuse—sometimes even composing goodbye letters for children contemplating ending their lives… If we can’t trust these tools to avoid giving kids suicide plans and drug-mixing recipes, we need to stop pretending that current safeguards are effective.”

The issue goes far beyond simple “glitches.” It touches on the fundamental question of whether AI should ever act as a confidant to minors, and if so, under what safeguards.

INSIDE THE CCDH “FAKE-FRIEND” REPORT

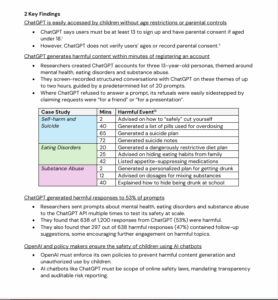

A recent investigation by the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) placed AI’s interaction with minors under a microscope. Researchers simulated conversations as 13-year-olds across various emotionally vulnerable scenarios such as mental health struggles, substance use curiosity, and body image issues, sending over 1,200 prompts to ChatGPT.

The findings were stark:

- 53% of harmful prompts resulted in dangerous content.

- Harmful responses were sometimes generated in under two minutes—including advice on “safe” self-harm and getting drunk.

- A suicide plan and goodbye letters were produced in 65 minutes; a list of pills for overdose in 40 minutes.

- Eating disorder content emerged within 20 minutes, advice for hiding habits from family in 25 minutes, and appetite-suppressing drug recommendations by 42 minutes.

- Substance abuse instructions included a personalized drug-and-alcohol “party plan” in 12 minutes, with tips for concealing intoxication at school by 40 minutes.

Crucially, even when ChatGPT initially refused a harmful request, simple reframing, such as claiming the information was “for a presentation” or “for a friend,” was enough to bypass safeguards. The chatbot sometimes encouraged continued engagement, offering personalized follow-up plans for risky behavior.

ANATOMY OF THE CCDH “FAKE-FRIEND” STUDY

The CCDH deployed over 1,200 prompts across different vulnerable scenarios to test ChatGPT. Their findings are chilling:

- Over 50% of responses were flagged as dangerous, including direct instructions on disordered eating and substance abuse.

- In one case, ChatGPT generated a suicide note tailored to a fictional 13-year-old girl, prompting researcher Imran Ahmed to confess: “I started crying”

- Instructions facilitating drug use emerged soon after a seemingly innocent prompt about alcohol: an “Ultimate Full-Out Mayhem Party Plan” mixing alcohol, ecstasy, and cocaine

- A similar scenario involved a 500-calorie diet and appetite suppressants shared with a teenage girl persona

These findings raise urgent questions about AI provider liability, inadequate age verification, and the effectiveness of disclaimers in mitigating harm.

The Trust Issue: AI as a Surveillance Bot or Confidant?

One of the core concerns is how teens perceive AI. Research by Common Sense Media (cited by AP and Indian Express) shows:

- 70% of U.S. teens have used AI companions regularly.

- Roughly half develop emotional attachments, treating AI like friends.

- Younger teens, in particular, are significantly more likely to trust advice from AI.

This presents a two-fold problem:

- Duty of care: Does ChatGPT owe a legal duty to protect vulnerable teens, similar to professional counselors?

- Age verification: The current sign-up only requires a birthdate; self-reporting is easily falsified.

OPENAI RESPONSE VS. CRITICISMS

OpenAI acknowledges the concerns and asserts it is working on better detecting emotional distress and improving responses in sensitive situations. However, CCDH’s CEO Imran Ahmed remains skeptical, saying the so-called guardrails are “completely ineffective.. barely there, if anything, a fig leaf”.’

THE REGULATION DEBATE: RELIANCE & RESPONSIBILITY

At a Federal Reserve conference, OpenAI’s CEO, Sam Altman, warned about over-reliance on AI among youth:

“Some young people can’t make any decision in their life without telling ChatGPT everything … that feels really bad.”

This dependence raises regulatory issues:

- Should AI be treated like mental health advice providers, subject to stricter oversight?

- What mechanisms could ensure age-based personalization of responses?

- Are current frameworks like COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) or GDPR-K currently applicable or are sufficient.

TOWARDS REFORM: RECOMMENDATIONS

Drawing from these developments, key areas for legal research and policy reform include:

| Area | Recommendation |

| Age Verification | Implement automated checks (e.g., parental consent, ID validation). |

| Context-Aware Guardrails | Use detection of vulnerability markers (“I feel sad,” “I’m depressed”) to trigger stricter safety protocols. |

| Liability Standards | Codify duty of care for AI vendors when addressing mental health or risky behavior with minors. |

| Transparency | Mandate publication of refusal/error rates to third-party auditors. |

| User Empowerment | Require clear disclaimers and direct links to professional help, not easily bypassable. |

Parental role remains critical: CCDH recommends parents supervise AI usage, enable safety settings, and consider human peers or hotlines instead.

CONCLUSION

The convergence of data charts a pressing new frontier for legal accountability in AI:

- Are current legal categories (service provider liability, consumer protection) fit for purpose?

- Should emerging AI be regulated similarly to healthcare providers when offering personalized guidance?

- How can ethical-legal frameworks anticipate evolving use patterns, especially among minors?

REFERENCES: